Commemorating the 250th Anniversary of the Founding of the Town of Cruz Bay in June of 1766

(Photo by Dr. George H. H. Knight) Knight Family Archive © All Rights Reserved

A New Vernacular: Cruz Bay’s Historic Post-Transfer Architecture

Although only a few examples of classic Danish Colonial architecture can be found in Cruz Bay, there is certainly no shortage of notable historical buildings throughout the town. Among these are a number of modest wooden vernacular cottages, which, up until not-too-long ago, represented a majority of Cruz Bay’s residential and commercial structures. St. John’s relatively isolated setting and late economic re-awakening, upheld traditional life-ways and prolonged its unique cultural integrity well into the second half of the twentieth century. What most of the western world regards as “modernization” was indeed slow to occur on St. John; public services and infrastructure – health care, sanitation, electrical power, telephones, and derivable road networks – did not begin to enter into the picture until the latter half of the 1940s and early 1950s. Even then, common commercial goods such as household appliances and manufactured building materials continued to be scarce and difficult to obtain, while their costs remained prohibitive for much of the St. Johnian population well into the post-Transfer period.

After the sale of the Danish West Indies to the United States in 1917, “Yankee” influences began to filter into Creole society, especially after a detachment of U. S. Marines was posted to Cruz Bay in the early 1920s. With this heightened outside presence came a growing sense of worldliness and a more cosmopolitan outlook. These perspectives quickly gained traction in the mid-to-late 1940s with the arrival of increasing numbers of Continental tourists and transplants, and the return of a first generation of local men from service in the U. S. Armed Forces. To the modern eye, the simple, timeworn vernacular wooden cottages of Cruz Bay began to appear passé or obsolete; concrete, reinforced with steel re-bar, and cinder block, soon became the preferred building method of the day. And with this shift in construction practices came a new architectural style influenced by a somewhat utilitarian World War II era United States military aesthetic – which in the VI often incorporated Latin-Caribbean (Puerto Rican) inspired flourishes.

(Above: postcard by The Art Shop, c.1960; Below: photo by David W. Knight Jr., 2015)

In response to this situation, local builders on St. John applied traditional skills and ingenuity to address mounting modern-day imperatives: local beach sand and pebbles were mixed with imported Portland cement to make concrete and plaster; native stone and old Danish bricks were used alongside manufactured cinder blocks and other commercial building components; kitchens with coal pots and braziers were fitted out with kerosene stoves and refrigerators; candles and oil lamps were replaced by battery operated torches and hard-wired electric lights run off gas-fed generators, and outside privies and the “night-soil system” gave way to indoor plumbing and septic waste systems.

It was during this post-Transfer period of transformation and renewal, between the 1940s and 1960s, that many of Cruz Bay’s historic structures were either significantly modified or created. Depending upon the skills, financial resources, and design sensibilities of the individual owners, the buildings constructed or upgraded during this era reflect a mingling of traditional Colonial West Indian and mid-twentieth-century American architectural design and building practices. This gives these structures a unique quality, which might best be labeled as Neo-Vernacular St. John Architecture. Of course the same forces were at play across the region during this period, and examples of similar buildings can be found throughout the broader Virgin Islands and Eastern Caribbean.

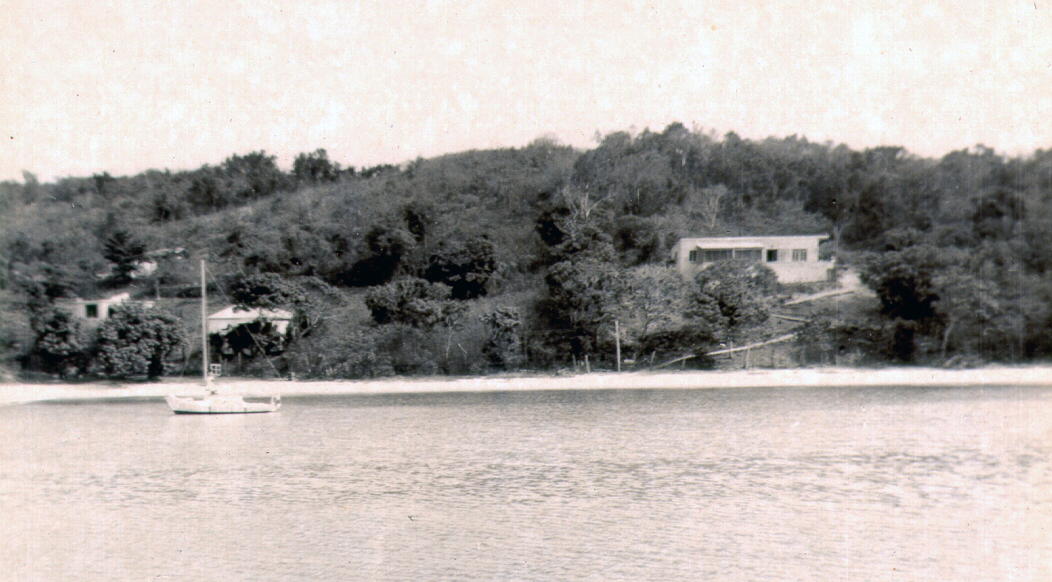

(Photo by Dr. George H. H. Knight, c.1958)

But, what is perhaps the single-most defining aspect of early post-Transfer construction on St. John, and what clearly distinguishes it as a discrete contextual era in which a unique vernacular form of local architecture came into being, is the ongoing use of West Indian built sailing craft as the primary means of transport for imported materials and supplies. Powered only by sail, these stout wooden cargo vessels supplied St. John with everything from building block and cement, to fuel oil and Coca-Cola. There are few places under the United States flag where the maritime traditions of seamanship and sail-borne freight were upheld for as long as on St. John, where commercial sailing vessels regularly called at the port of Cruz Bay through the 1960s.

(Photo by Dr. George H. H. Knight)

It must be noted that structures built during the early post-Transfer time frame are among the most critically endangered of Cruz Bay’s (and the broader Virgin Islands’) cultural resources. Not quite old enough to be popularly perceived of as historic and worthy of preservation, yet just old enough to be looked upon as antiquated and/or out of date, they are presently susceptible to unmindful demolition to make way for further development. It is my hope that the recognition of Cruz Bay as the fourth Historic District within the Territory will help highlight, and call greater attention to, our community’s need to embrace these buildings as valued components of Cruz Bay’s rich architectural heritage.

It was not until the era of traditional sailing cargo vessels came to an abrupt end around 1970, that the present period of rapid, wide-spread development on St. John truly began. This nearly half-century long rush of unchecked residential and commercial growth, has largely been made possible by the introduction of regularly scheduled roll-on-roll-off barge traffic carrying bulk freight containers, ready-mix concrete trucks, and specialized heavy equipment.

(Photo by David W. Knight Sr.)